Little black book vs blue blood 192

Read Little Black Book vs Blue Blood Chapter 100 online for free at MangaHub.io. Real English version with high quality. Fastest manga site, unique reading type: All pages – scroll to read all the pages

Niadd is the best site to reading Little Black Book Vs Blue Blood Chap. 192 free online. You can also go

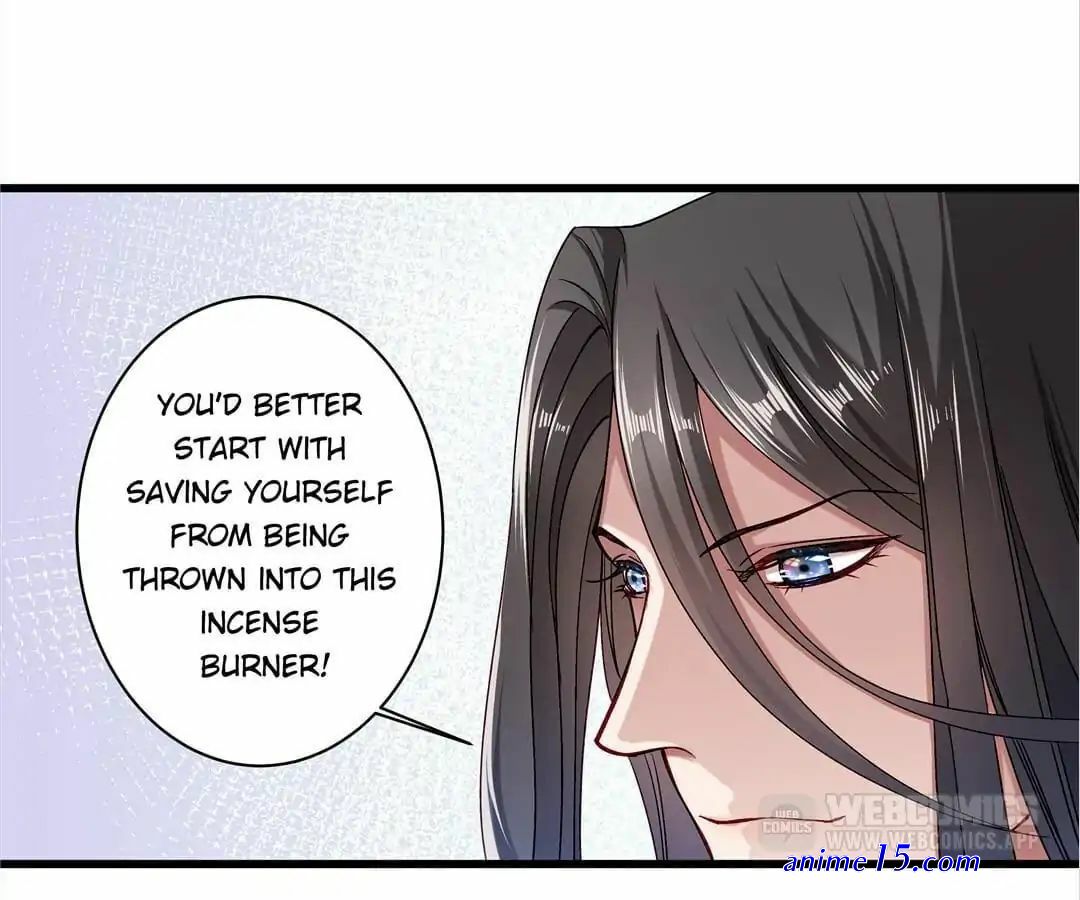

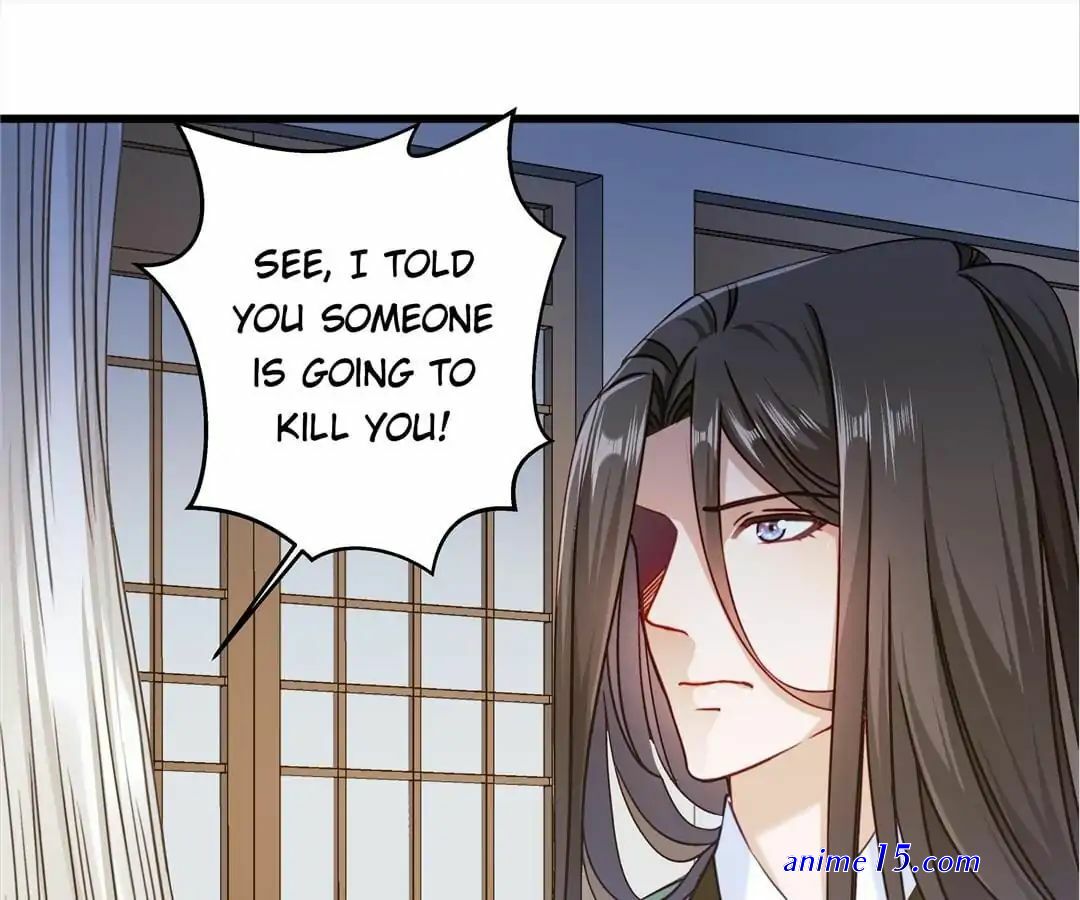

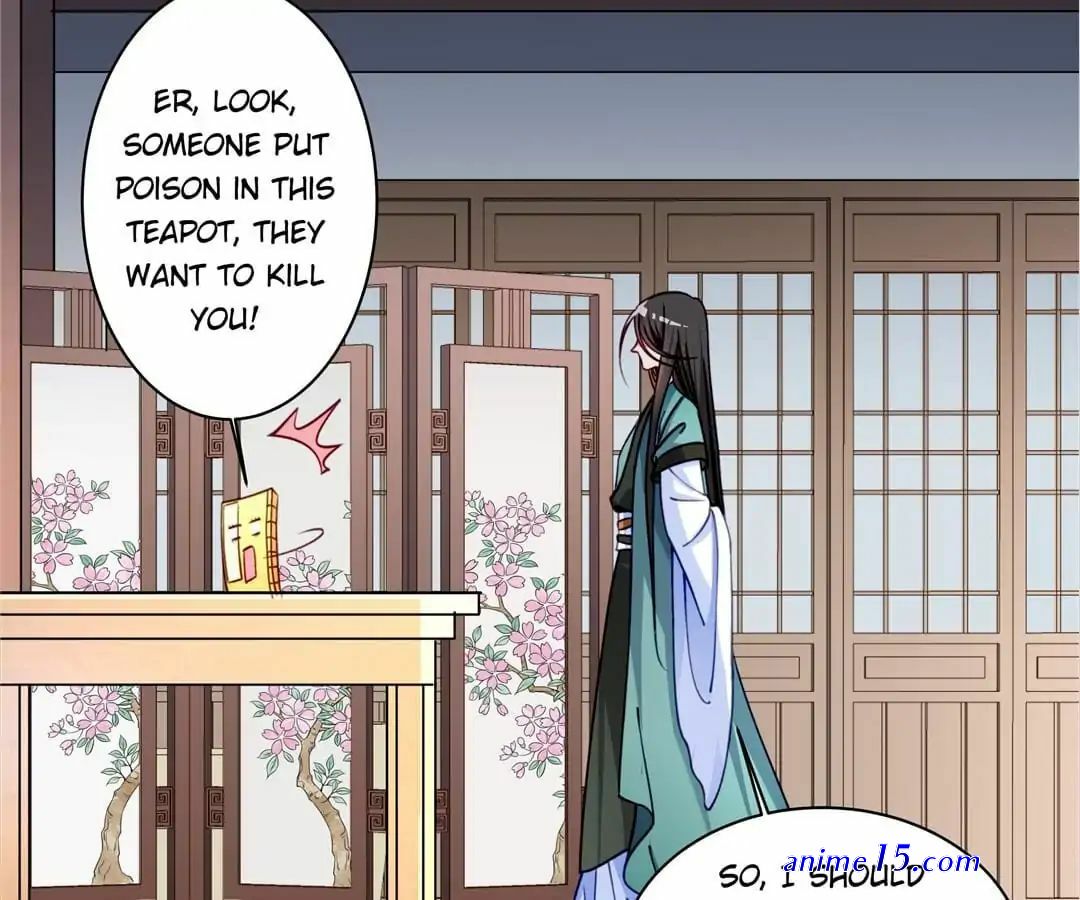

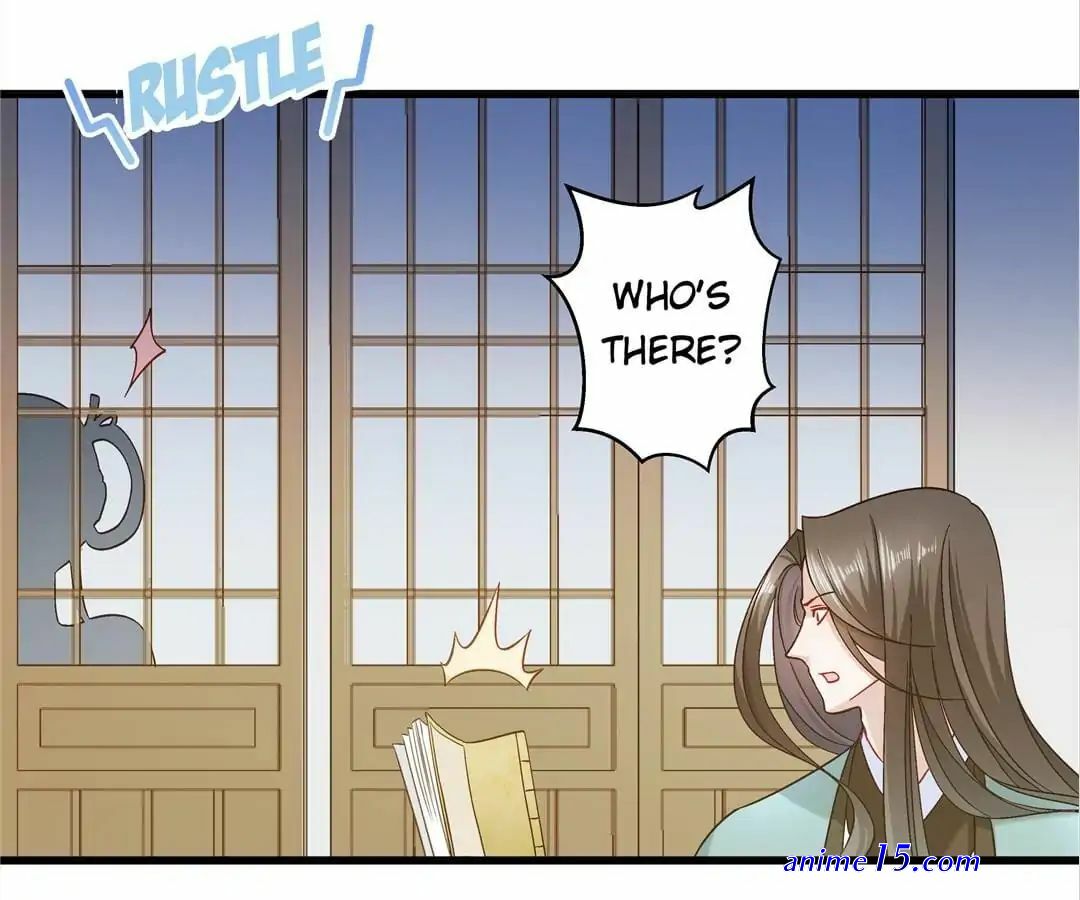

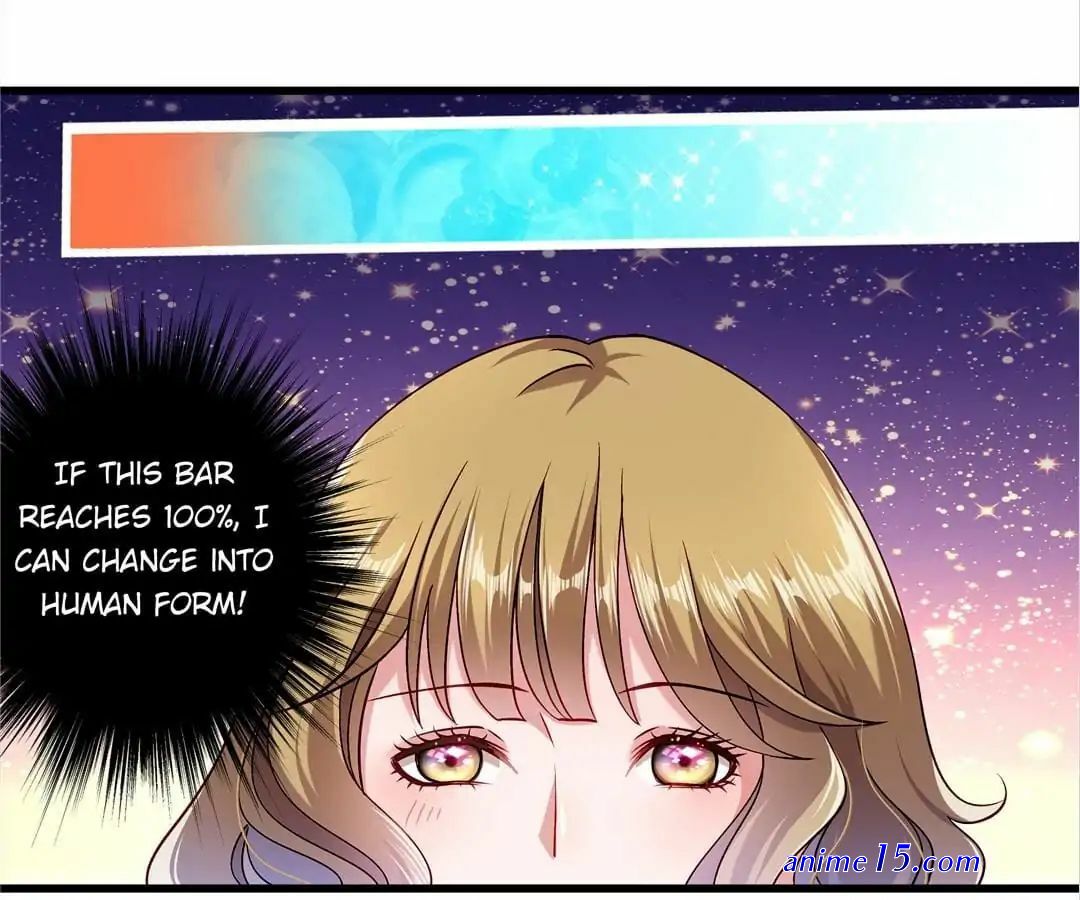

All of a sudden, I traveled through time and space to be a Little Black Book, bearing the mission to grant Prince Kang a baby, and only after that, could I travel back. It's a journey to get him back on the road! But it's technically difficult to help a delicate but handsome man learn how to flirt with the beauties. Follow my lead, let's set out on a magical time travel!

Niadd is the best site to reading Little Black Book Vs Blue Blood Chap. 190 free online. You can also go

Niadd is the best site to reading Little Black Book Vs Blue Blood Chap. 156 free online. You can also go

Niadd is the best site to reading Little Black Book Vs Blue Blood Chap. 187 free online. You can also go

NineAnime is the best site to reading Little Black Book vs Blue Blood Chapter 100 free online. You can also go

On November 16, 1966, the commanding officer of Eriksson’s platoon, a Negro lieutenant, Harold Reilly (whose name, like every soldier’s name in this account, has been changed), assigned him as one of five enlisted men who were to make up a reconnaissance patrol, its mission to comb a sector of the Central Highlands for signs of Vietcong activity. Testifying later in court, Lieutenant Reilly characterized the mission as “extremely dangerous,” and said that to carry it out he had picked members of the best of the four squads in the platoon. Special care had been taken with the operation, he stated, since it had been conceived by the battalion command, a higher echelon than the company command, to which Reilly was ordinarily responsible. Explaining his choice of the patrol, Reilly testified, “These people, I felt, knew what they were doing, and a second reason was because the company commanding officer asked for good people.” On the following afternoon, November 17th, the members of the newly formed patrol met in a corner of the platoon’s headquarters area, near the village of My Tho, where, relaxed as they stood or sat on the ground, they listened to a briefing from their leader, who was seated on a low stool. He was Sergeant Tony Meserve, a slim, black-haired man of medium height who was twenty years old and came from a town in upstate New York, near the Canadian border. According to Eriksson, Meserve, who was assertive and confident, was both the patrol’s youngest soldier and its most experienced one, being a volunteer of three years’ standing who had fought in Vietnam for a year and had been decorated several times; he was due to go back to the United States in a month. The group’s second-in-command was Ralph Clark, a corporal who came from a town near Philadelphia. He was twenty-two, a stringbean in physique, and blond, with eyes that were a pale, cold blue. Again according to Eriksson, Clark was given to quick movements and to seemingly abrupt decisions that reflected Meserve’s thinking in an exaggerated form. The two other G.I.s in the combat team were a year younger than Eriksson, who was then twenty-two. They were cousins named Diaz—Rafael, known as Rafe, whose home was near Amarillo, Texas, and Manuel, who came from a town some distance north of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Eriksson remembers Rafe as a tall, swarthy, round-faced man with a disposition that was naturally sunny and amiable. As for Manuel, who was fair-skinned and stockier than his cousin, his manner was on the jumpier side. Like Clark, he was given to quick movements, but his behavior had nothing to do with embellishing Meserve’s thinking. Manuel showed no initiative in that regard, Eriksson told me, his attitude toward authority being simple and automatic: he heeded it devoutly. In mild contrast, Rafe was capable of questioning authority, Eriksson said, but he generally wound up by going along with whoever seemed to be the leader—“just to keep from making trouble.”

Eriksson now lapsed into the longest of his silences with me, and when he spoke again, it was, for him, at great length. “When Mao saw me come into the hootch, she thought I was there to rape her,” Eriksson said. “She began to weep, and backed away, cringing. She looked weary and ill, and she seemed to be getting more so by the minute. I had a feeling she had been injured in some way—not that I could tell. She had her black pajamas on. I gave her crackers and beef stew and water. It was her first food since she’d been taken away from her hamlet—it had been still dark then, and here it was the middle of the afternoon. She ate, standing, and it was whimper, then eat, whimper, then eat. She kept looking at me, as though she was trying to guess what my game could be. When she finished eating, she mumbled something in Vietnamese; maybe it was ‘Thank you’—I wouldn’t know. And I told her, in English, ‘I can’t understand you.’ I wanted to tell her other things. I wanted to say, ‘I apologize to you for what’s happened, but don’t ever accept my apology or anyone else’s for that. Please don’t ask me to explain why they did it. I’ll never know. You’re hurt, I can see, but how are you? I mean, if I let you go, do you think you can make it home?’ I wish Mao and I could have talked,” Eriksson said, his voice tightening. “She might have helped me know what to do, instead of my having to figure it out alone—it was her life that was at stake. I stepped outside the hootch to be by myself awhile, and out there I could hear the muffled noise of artillery off in the distance. I had no idea where my unit was. I didn’t know then that they were four hundred metres away, at the top of Hill 192, or that it would be a whole hour before they returned. It might have influenced my thinking if I’d had that information, but I’m not sure. As a disciplined soldier, I knew I wouldn’t abandon the weapons in the hootch to the enemy, but, just the same, I was dizzy with thinking how to save Mao. I thought again of letting her go, but what would I tell Meserve when he got back? That this weak, coughing girl had overpowered me? Besides, she was in no condition to reach home or anywhere else. Then I thought of taking off together with her. We couldn’t have gone very far, I realized, but it was going to be dark soon and we might find a hideout somewhere in the brush. After that, we’d have to stay out of sight until the third day of the patrol’s mission—that was the day the patrol was supposed to rendezvous with another unit for fresh supplies. I knew the rendezvous spot, and if Mao and I could show up there at the right time, there was no question in my mind but that the fellows in the resupply squad would help us both. But I couldn’t think any of my brainstorms through. I knew I had cut myself off from the rest of my patrol, refusing to go into that hootch, and I had this idea that the fellows were watching the place from the brush, waiting for me to make just one false move with Mao. I had this picture that when we did, they’d fire at us, or, at least, Meserve would have me up on charges of desertion. The guys would back him up, of course. They’d say there had never been a girl with the patrol, and I’d be left looking crazy.”

Mao’s sister, Phan Thi Loc, appeared as a prosecution witness, her very presence irrefutable evidence that Mao was not in fact living happily in her hamlet. Through an interpreter, Loc related that after the patrol finished with their hamlet, she and her mother had searched desperately for Mao. Accompanied by troops of the South Vietnamese government, the two women had eventually come to the hootch on Hill 192, where they had found Mao’s brassiere, flecked with blood; the troops had burned down the hootch. Loc’s mother was now missing. The Vietcong, Loc said, had abducted her, accusing her of having led South Vietnamese forces to a V.C. munitions cache on Hill 192. Loc and her father had moved from their native hamlet; they now lived in a village several miles from there.

A wave of immigration occurred in the 1920s, with Black people from the Caribbean coming to work in the steel mills of